What Are the Peaple Doing to Prevent the Indian Ocean Tsunami From Happening Again

The Australian Tsunami Warning Organization

While Australia's chance is considered lower, it is nonetheless vulnerable to seismic sea wave threat from both the Pacific and Indian oceans, with waves able to arrive on our mainland in as little as two hours.

Commonwealth of australia was fortunate not to be in a direct path of the tsunami wave energy from the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami, with nigh of the free energy travelling west from Sumatra. However, a major earthquake south of Java could focus tsunami moving ridge energies on the west coast of Australia. Similar threats exist for the e coast of Australia.

'In response to the devastating 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami and to mitigate confronting the risk of impact on Australia, the Australian Government pledged to develop an Australian Tsunami Alarm System'

In response to the devastating 2004 Indian Body of water Tsunami and to mitigate against the risk of impact on Australia, the Australian Government pledged $68.8 1000000 in the 2005-06 Budget to develop an Australian Tsunami Alarm System (ATWS) over four years. The system would aim to:

- provide a comprehensive tsunami warning system for Australia

- back up international efforts to institute an Indian Sea-wide tsunami alert arrangement, and

- contribute to the facilitation of tsunami warnings for the southwest Pacific region.

Over the following years, significant work was contributed to develop a alarm system for Australia and the Indian Ocean region.

The institution of the ATWS utilised existing scientific and technical expertise at Geoscience Commonwealth of australia, the Bureau of Meteorology, and Emergency Management Australia, also every bit the diplomatic leadership of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Merchandise.

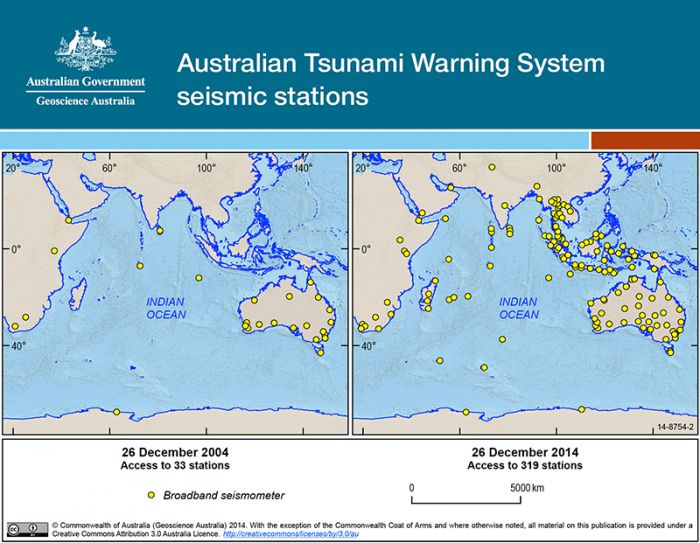

Geoscience Australia was provided funding to upgrade existing seismic stations - instruments used to record seismic activity across the globe, build new seismic stations (both within Australia and overseas), and to access real-time digital seismic information from new and existing international seismic networks. The organization also established a 24/seven performance centre.

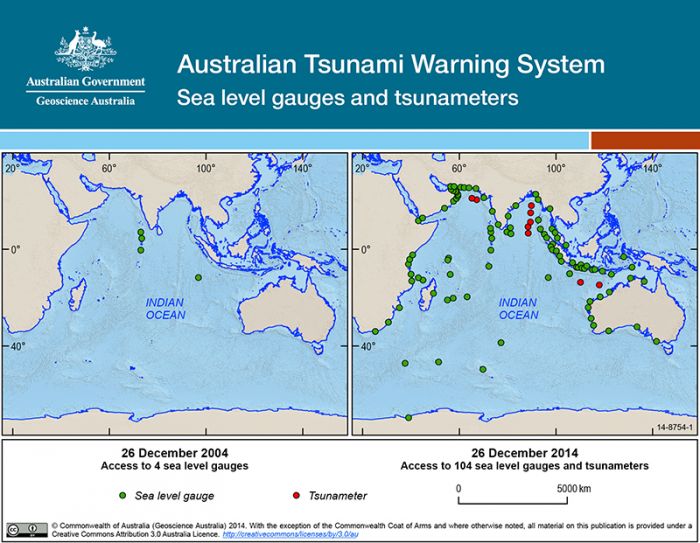

Bureau of Meteorology was funded to upgrade existing tide approximate sea level stations - instruments used to mensurate surface wave height and variation, build new tide gauge stations within Australia and overseas, and to install new tsunameter buoys - instruments designed specifically to monitor energy variance in deep water - located in deep ocean locations about subduction zones. The Bureau built on its existing 24/7 operations and infrastructure to develop a tsunami forecasting and warning capability.

Emergency Management Australia (inside the Chaser General's Department) was funded to develop a general community understanding of the tsunami threat to Commonwealth of australia and to develop and nowadays a program of tsunami awareness and grooming for emergency managers, industry and the general community.

In October 2008, the designated Joint Australian Tsunami Alarm Middle (JATWC) - 24/7 monitoring and warning functioning centres in Canberra and Melbourne - were officially opened and fully operational. The JATWC is Australia'due south authority on convulsion and seismic sea wave monitoring and warnings, with the infrastructure to provide accurate and timely advice for Australia and its offshore territories.

Where nosotros are now

Australia'south world-class tsunami warning arrangement at present operates 24 hours a day and is a major component of a multinational Indian Ocean seismic sea wave alert system.

At the time of the 2004 Indian Sea Seismic sea wave, Commonwealth of australia relied on the existing Australian Tsunami Alarm Organisation, which provided a limited notification and alerting adequacy to emergency services and relevant regime.

'Commonwealth of australia has a comprehensive tsunami warning system for the nation including its offshore territories, and supports the Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning System'

At that place were no mitigation and response strategies in place at the customs level; Geoscience Australia had 33 seismic stations (developed for domestic earthquake monitoring and alert services); and the Bureau of Meteorology had 26 sea level monitoring stations, simply with very limited capability to access the data in existent-time. There was no seismic sea wave forecasting adequacy.

Now, Australia has a comprehensive tsunami warning arrangement for the nation including its offshore territories, and supports the Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning Organization (IOTWS).

Within ten minutes the Joint Australian Tsunami Warning Middle (JATWC) can now detect and notify of an earthquake with the potential to generate a seismic sea wave. Within a farther ii-five minutes, the JATWC tin forecast tsunami threat and potential impacts, providing the public, media, emergency managers and other relevant regime with tsunami warnings.

Geoscience Australia now have access to over 300 seismic stations beyond the earth, enabling comprehensive analysis, and Bureau of Meteorology at present operate 44 coastal sea level stations and 6 deep-ocean tsunameter buoys, monitoring ocean level in real-time in the Indian and Pacific oceans. The Bureau of Meteorology also have access to more than 100 coastal ocean level stations and 46 tsunameter buoys operated by other countries in our region.

In October 2011, Commonwealth of australia, forth with India and Indonesia, became 1 of iii countries providing real-time, rapid-response tsunami information to countries bordering the Indian Sea. This communication supports these countries in issuing timely and confident warnings to their affected coastal communities.

In April 2013, an interim seismic and sea level monitoring system ceased and the Indian Ocean region had an independent tsunami warning capability. The IOTWS is made up of contributions from Member States of the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO around the Indian Ocean - mainly Commonwealth of australia, India, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Malaysia and Thailand. Significant contributions were likewise fabricated by the U.s.a., Nippon and Germany.

Australian Tsunami Warning Organisation Sea level gauges and tsunameters

Australian Tsunami Warning Organization seismic stations

10 years later the Indian Ocean Tsunami:

What have nosotros learned?

Professor Phil Cummins is an convulsion seismologist whose enquiry focuses on earthquake and seismic sea wave hazard, the rupture properties of subduction zone earthquakes, and the active tectonics and crustal structure of Republic of indonesia.

Professor Phil Cummins is an convulsion seismologist whose enquiry focuses on earthquake and seismic sea wave hazard, the rupture properties of subduction zone earthquakes, and the active tectonics and crustal structure of Republic of indonesia.

Though no 1 realised it at the time, the 2004 Sumatra-Andaman earthquake was the first in a series of massive earthquakes to shake the globe. At magnitude ix.1 information technology is among the three largest earthquakes e'er recorded since instrumental recordings began at the turn of the 20th century. The following seven years saw the occurrence of another iii of the x largest earthquakes ever recorded (including the giant earthquake and tsunami in northeast Japan in 2011). This sequence of four megaquakes occurring over 2004-11 rivals another series that occurred over 1952-1965, when another four of the ten largest earthquakes always recorded occurred around the Pacific Rim - including a magnitude 9.5 offshore Republic of chile in 1960 - the largest earthquake ever recorded.

Nosotros still know very little about why megaquakes occur in clusters like this. One explanation for the recent big events is the mechanism of stress transfer, in which the Sumatra subduction zone 'unzipped' in a serial of massive earthquakes that ruptured sequentially from northwest to southeast from 2004-07. But this does not explain the presence of a large 'gap' in central Sumatra. In this department the recurrence of earthquakes that occurred in 1797 and 1833 was - and still is - widely anticipated, not just by scientists but past the many residents of the city of Padang, who are crowded into a low-lying coastal strip that will nigh certainly exist inundated by the resulting seismic sea wave. However, the 'unzipping' of the subduction zone mysteriously skipped this segment during the 2004-07 sequence. Besides, we don't know what role, if whatever, the 2004 Sumatra Andaman earthquake may have played in triggering afar events like the 2010 Maule, Chile and the 2011 Tohoku, Nippon earthquakes. And nosotros don't know if the present sequence of megaquakes is at an terminate.

'If the Indian Sea Tsunami occurred today, the number of lives lost would exist significantly less than the devastating number of fatalities seen in 2004'

What we do know is that the 2004 Sumatra Andaman earthquake generated a massive tsunami - the Indian Ocean Tsunami - that killed over 227 000 people, more ten times the number of lives lost in the remaining 9 of the ten largest earthquakes combined (the full fatalities for these was nearly 21 000). Why did the Indian Ocean Seismic sea wave kill so many compared to other earthquakes of similar size? First, the convulsion occurred merely offshore of a major population heart. The population of Banda Aceh earlier the seismic sea wave was over 264 000, and these in addition to the populations of towns along the western coast of Aceh were severely affected by the tsunami. The town of Lhok Nga, where observations of seismic sea wave run-up height reached over 30 metres, had a pre-tsunami population of 7000, reduced to 400 after the tsunami. Banda Aceh itself suffered over 61 000 fatalities, almost 25% of its population. In all, Indonesian fatalities are idea to number at least 167 000 (estimates range as loftier as 220 000), over 70% of the total Indian Ocean Tsunami fatalities. Fifty-fifty when only the Indonesian fatalities are considered, the Indian Ocean Tsunami is the world's deadliest tsunami disaster.

But the Indian Ocean Seismic sea wave was unique among seismic sea wave disasters in the calibration of fatalities caused on a regional scale. Because the rupture extended far north from Sumatra into the Andaman Sea, both India and Sri Lanka in the west, and Thailand in the east, were direct in the path of the main feather of tsunami free energy. In addition to the 167 000+ fatalities in Republic of indonesia, over 61 000 died in Sri Lanka, Republic of india and Thailand. Around 2000 Europeans, many tourists visiting Thailand, were killed, including over 500 each from Sweden and Germany. 26 Australians also died while overseas in southeast Asia, and dozens were swept to sea by the large waves and potent currents generated when the seismic sea wave reached Australia's western declension.

In add-on to the large littoral populations exposed to the tsunamis, the major contributing factor to the massive loss of life was a lack of preparedness. A large tsunami in the Indian Ocean was non without historical precedent. The tsunami generated past the eruption of Krakatau in 1883 killed over 35 000 people along the Sunda Strait separating Coffee and Sumatra. Massive earthquakes in 1797, 1833 and 1861 had occurred off Sumatra, and both the earthquakes and the tsunamis they generated were well documented by Dutch historians. Even so, these earthquakes had occurred well south of Aceh. While these large local tsunamis destroyed coastal villages, there were at that fourth dimension no major population centres along this part of the Sumatra coast. The population of Padang, at present over 800 000, was but 4000 in 1797. Furthermore, the ruptures of these earthquakes were too far south to have affected Thailand, India and Sri Lanka. So, while there had been big earthquakes and tsunamis in the Indian Bounding main, there was no historical precedent for a seismic sea wave affecting big coastal populations. As a consequence in that location was no alert system, and coastal populations did not know to evacuate depression-lying coastal areas in the event of a large earthquake. An exception was the island of Simeulue, to the west of Aceh, where an oral tradition preserved from feel of a smaller tsunami in 1907 caused residents to run to higher ground when they felt the earthquake, saving many lives. In hindsight, information technology seems clear that amend preparedness could have prevented many 10 000s of deaths.

You demand to upgrade your browser and have javascript enabled to view this video.

Much has inverse in terms of preparedness in the ten years since the 2004 Indian Sea Tsunami. A warning system for the Indian Ocean has been established, and many at-adventure populations are well aware of the danger of tsunamis, and in many cases are drilled in evacuation procedures. The tsunami take a chance is taken seriously even in subduction zones that have not historically experienced a megaquake. Were an event similar the Indian Sea Tsunami to occur again today, information technology seems extremely unlikely that the fatalities caused at regional and greater distances would exist anywhere nigh the scale of the decease toll in India, Sri Lanka and Thailand in 2004. This is because, with lead times of several hours between detection of an issue and its impact on regional or afar shores, conventional tsunami warning systems are generally very effective.

Withal, it is of import to bear in mind that over lxx% of the Indian Bounding main Seismic sea wave fatalities, 167 000 or more, were killed by the local tsunami that arrived on the shores of Sumatra within minutes afterwards the convulsion rupture. Local tsunami warning remains a hideously difficult problem, in which decisions must be made and warnings disseminated within minutes, and coastal populations must evacuate within 10s of minutes. This in urban areas that are congested at the best of times, and possibly impassable later on suffering the effects of a major earthquake. Imitation alarms are inevitable, and the consequent erosion of public confidence in alert systems are difficult to avert. Nippon'southward experience of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and seismic sea wave serves notice that even in the presence of the best warning systems, sophisticated communications and seismic sea wave-aware coastal communities, local tsunamis are withal able to inflict massive fatalities. Indonesia and its neighbours can minimise losses by strengthening all these elements of mitigation, simply information technology is however a large challenge to completely avert high fatality events.

Tsunamis are not the merely hazard that can cause massive fatalities. Big as the Indian Body of water Seismic sea wave death toll in Aceh was, there are at least twoscore cities in Republic of indonesia larger than Banda Aceh, including the megacity of Jakarta. By virtue of location many of these cities may be relatively sheltered from tsunamis. Only they, like many of their cousins in neighbouring countries, have highly concentrated urban populations that typically reside in poorly constructed, masonry homes decumbent to collapse if subjected to strong earthquake ground motion. Such strong ground motion does not have to come from a megaquake: 316 000 deaths were acquired in Port-au-Prince by the 2010 Haiti earthquake, with a magnitude of 'only' 7. Virtually every city in the chugalug of active tectonics stretching from the Himalayas, through Bangladesh and Burma, Indonesia and the Philippines, likewise as much of Papua New Guinea, could potentially experience such an earthquake.

Is a massive-fatality earthquake/tsunami outcome in the Southeast Asian region inevitable in the 21st century, and if so are mitigation efforts pointless? The explosion in population and urbanisation over the latter half of the 20th century in such a seismically agile area would indeed seem to make the eventual occurrence of such a mega-disaster all but certain. Then the question then becomes "are mitigation efforts worthwhile"? Admittedly. If the Indian Sea Tsunami were to occur today, it is likely that the regional alert system would reduce the 61 000 fatalities at regional and greater distance to at nigh a few 1000. Even if local warning and evacuation procedures were only partially successful, they could reduce fatalities to tens rather than hundreds of thousands. If the effectiveness of seismic sea wave alert systems and community awareness can exist maintained over the long term, and if this can be combined with improved building practices, hundreds of thousands - if non millions - of lives tin can be saved. But we need to draw upon these efforts now, while memories of the Indian Body of water Seismic sea wave are still fresh and it is still possible to aqueduct some of the region'south recourses into mitigation efforts. It's the best thing nosotros tin can practise to give meaning to such a devastating natural run a risk that changed the lives of so many on that solar day in 2004.

Source: https://www.ga.gov.au/news-events/features/ten-years-on-2004-indian-ocean-tsunami

0 Response to "What Are the Peaple Doing to Prevent the Indian Ocean Tsunami From Happening Again"

Post a Comment